[I’ve prepared the following post to go with a brief talk I’m giving on March 1 at UC Berkeley’s Academic Innovation Studio for a panel discussion on “Beyond Hype, Hysteria, and Headlines: Strategies to Address Media Literacy Gaps in the Classroom.”]

Shortly after she became a grandmother, the writer Anne Lamott came up with a brilliant acronym as a reminder for herself. Any time Lamott felt the urge to offer unsolicited (and probably unwelcome) parenting advice to her son and daughter-in-law she would try to stop herself by thinking:

W.A.I.T.

Which stands for “Why am I talking?”

The acronym works beautifully in its two-fold way by first reminding one to pause and then to think before speaking. Though she intended it for her own use, and subsequently as a suggestion for other grandparents, I’ve found it helpful to employ as a parent of a pre-teen as well as in meetings at work and in conversations with friends and loved ones.

Inspired by Lamott, and knowing I wanted my undergraduate students at Berkeley to do a little thinking about the “fake news” that’s much discussed in the real news these days, I came up with an assignment for them centered around another acronym:

W.A.I.S.T.

Which stands for “Why Am I Sharing This?”

Guiding Students Through the Morass of Fakery and “Fakery”

As many media observers have noted, fake news has become a kind of catch-all term in the past few months to harness information reported and shared online that is entirely or partially made-up, and which could constitute anything from straight-up propaganda to biased half-truths to cynical attempts to profit from people’s mindless, emotional clicking to sharp satire and on and on until we get to meta moments like this piece of performance art when earnest news commentators are rightfully sussing out fake news purveyors who, in their turn, prove the point of how easy it is for fake news to go viral.

And that’s to say nothing about the most troubling category of fake news: the news that the current president categorizes as “fake” not because it’s not factual or well-sourced but because he doesn’t like the story.

Into this breach stepped the students in my second-semester freshman reading, composition, and research class. As in thousands of other college classes across the country, my students always learn to practice careful critical assessment of source material. This is essential not only to their work while in college, but also to their future as engaged, productive citizens. Since my current group is studying issues around the Internet, social media, and the human-machine interface generally, it was a natural fit to ask them to spend some time discussing and then evaluating some of the news they themselves were inclined to share in online spaces.

We first discussed what they took “fake news” to mean, and looked at some samples of things that were flat-out lies, such as this meme that was widely circulated in many forms and on many social media sites prior to the election last November:

Source: Snopes

As has been widely reported, Donald Trump never said this. It didn’t stop the meme, even after it was debunked, from being shared again and again on social media by Trump’s detractors who desperately wanted it to be true. As my students noted, it’s difficult to figure out who originated many memes, but whoever created this one did a bang-up job of trying to capture a Trumpian tone to the quote that made it seem potentially real.

My class also looked at this bit of fake news about President Obama supposedly banning the Pledge of Allegiance in schools that stirred up predictable outrage amongst those who didn’t like him. Those same people presumably ignored whatever internal “Really?” voices they possessed (not to mention the funky URL with the extra “co”) and instead liked, shared, or otherwise reacted to this fake post on Facebook some 2.2 million times as of mid-November:

Source: Refinery29

Among the key things to note about these two samples of fake news are that each of them went viral because of the emotions they stirred among Trump’s and Obama’s detractors, respectively. Many people who were pleased to see confirmation of their own biases, and who were spurred on by the controlling fervor of their emotions and the satisfying immediacy of the social media interface, shared and reacted to this fakery quickly and without much thought.

Clearly it’s time we all slowed ourselves down a bit.

The Assignment

After the above discussion, I asked my students to read this excellent article by the journalist Brooke Berel that usefully frames in the problem of fake news, provides historical context and helpful links (including this list of fake news sites from Melissa Zimdars of Merrimack College), and points to steps that journalists, tech companies, and we, the public, can take to ensure that fake news doesn’t metastasize into a permanent condition.

My assignment, which you can see here (why-am-i-sharing-this) was a simple one.

I asked my students to pick two items from their social media feeds that they’d be likely to share with others (or which indeed they had already shared) without too much thought. Whether a joke or apparently serious news, whether an article or a meme or a video or a GIF, the two pieces they picked had to have some facts or claims that would need to be verified. Then I asked them to write up their assessments of each piece in five steps:

- Describe what it is.

- Explain why you’d be inclined to share it quickly.

- Identify and carefully evaluate the source: its origins, its credibility, its biases, its truth.

- Consider your audience: how would they react? what benefits or problems might arise from sharing this post so quickly?

- And then, knowing what you know now, would you still share the post, and what have you learned by doing this exercise?

The students picked a wide range of material and revealed themselves to be astute evaluators of truth on social media (contrary to what some studies of their generation have found), readily identifying clickbait and things that would stir social media users in particular ways. However, there was also evidence that some of them needed more help in assessing not only the factuality of material but also the context in which that material was situated and how that shaped the message. This was to be expected–most of my students are college freshmen, and people of any age can make these types of mistakes. But it also pointed up a key thing to consider about the problem of fake news: in school assignments, students make these mistakes even when they are keyed to think and act more carefully and critically. In everyday discourse on social media, where speed and emotion are king, what chance does the truth have?

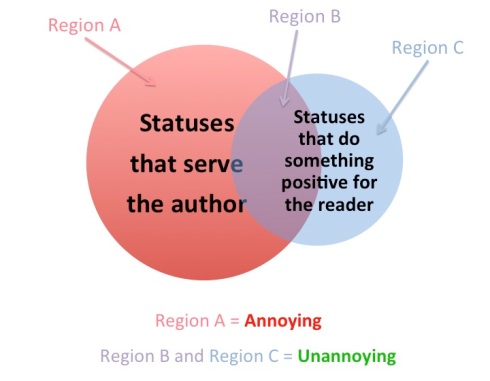

Another thing that stood out in the students’ responses was their acute awareness of their immediate audience on social media: Not only (or even primarily) “Is this post true?” but “Will my followers and friends like it?” In doing so, they seemed to enact their own versions of this graphic representing “How to be unannoying on Facebook”:

Source: WaitButWhy

Intuition and the Mind:

A Few Obvious and Yet Important Takeaways for Fighting Fake News

After the students had completed the assignment, we talked about some of the things they thought we all should do to better evaluate news and “news” that is shared on social media. Working in small groups, they each came up with lots of good suggestions for making classic critical moves of evaluating authors, media outlets, and interest groups; cross-checking facts; following trails to original sources; being aware of confirmation bias; sniffing out doctored images and sketchy web site design; relying on fact-checking sites and on distinguishing credible sources from non-credible ones, and so forth. I was pleased to see them suggesting many of the same steps recommended by the UCB Library when it issued a guide to identifying fake news a couple of weeks later.

An amusing contrast emerged when one group listed the advice to “Use your mind!” when on social media, while across the room another group advised people to “Use your intuition.” While the assignment and our debriefing of it were largely focused on doing the former, the latter was indeed an important step in the process of assessing an item’s veracity. It just shouldn’t be the only one.

So, distilling the students’ very concrete findings and that mingling of mind and intuition, I come to the following steps for asking and enacting W.A.I.S.T. (“Why Am I Sharing This?”) not just in scholarly work but, especially, in everyday social media use, enabling a pause to think before sharing, liking, or reacting in whatever way:

*The more emotional you are, the more you should pause.

*If it’s not a credible source you know you can trust, you should pause.

*If the piece speaks deeply to your own biases, you should pause. Twice.

*If liking/sharing/reacting is mostly about making yourself feel better, you should pause. (See Venn Diagram above.)

*If you haven’t carefully considered how your audience will react to the news, you should pause.

*Do you want the site you’re sharing or liking to make money from your sharing and liking? No? Then you should pause.

*Have you actually read or watched the thing you’re sharing? No? You know what to do.

You get the idea. Like Anne Lamott, the grandmother aspiring to restraint, we all need to take a moment to WAIT before reacting, then ask WAIST, and then, and only then, should we act. Remember that most of the time on social media we are not in read-and-react situations of imminent danger: we are not in a war zone, on a dark street corner at night, or about to be sacked by a 300-pound lineman. Most of us are sitting on our couch at home, getting stirred up by the little machine in our hand.

Speaking of machines…

…A Coda from E.M. Forster

For several years, I’ve had students in this same class read E.M. Forster’s prescient short story, “The Machine Stops,” which was first published in 1909. (I’ve previously written about Forster’s story and its relevance for our time elsewhere on my blog.) In the story, the people of a futuristic society live entirely underground and rarely move or leave their hive-like “cells,” such that their bodies have become “lump[s] of flesh.” The most common activity is sitting alone in one’s cell before a screen, remotely connected by a central, god-like Machine to thousands of other residents, all of them incessantly listening to and giving lectures on various “ideas” that aren’t ideas at all.

At one point in the story, an influential lecturer whose area of expertise is the French Revolution gives some advice to his sedentary, isolated listeners that captures the ethos of the soon-to-perish Machine civilization. Like so much of Forster’s story, the lecturer’s absurd advice to his somnolent audience offers us an all-too-relevant warning for our own time:

“Beware of first- hand ideas!”….“Let your ideas be second-hand, and if possible tenth-hand, for then they will be far removed from that disturbing element—direct observation. …You who listen to me are in a better position to judge about the French Revolution than I am. Your descendants will be even in a better position than you, for they will learn what you think I think, and yet another intermediate will be added to the chain. And in time…there will come a generation that has got beyond facts…a generation…which will see the French Revolution not as it happened, nor as they would like it to have happened, but as it would have happened, had it taken place in the days of the Machine.”