I’ve written the following post to accompany (and extend) my talk on “Cultivating a Digital Reading Mindset in First-Year Composition” that I’ll be giving this Friday at the 2017 Conference on College Composition and Communication in Portland, Oregon (Session I.38).

While I’m primarily directing this toward an audience of college instructors, I hope that teachers at all levels—as well as anyone interested in the differences between print and screen reading and how to become better at the latter—will find something useful in it.

To find your way to any of the sources cited below, as well as to a number of other articles, studies, and books on this subject, I encourage you to visit this annotated bibliography of sources on digital reading that is available on the websites of UC Berkeley’s College Writing Programs and UCB’s Center for Teaching and Learning. (P.S. Thanks to Jason B. Jones of Trinity College for this shout on the ProfHacker blog of The Chronicle of Higher Education.)

Facing the Screen Honestly

My appeal to you today depends, in part, on how you feel about reading on screens and how you approach that subject with your students, especially those students who are early in their college careers:

Are you one who asks (or allows) your students to read many, or most, of the texts for your course in digital form, both on- and offline?

Or do you tend to require your students to read most, or perhaps all, of the texts for your course in printed form?

If you are in the first group, I ask you to consider how much time you spend in your class explicitly addressing the practice of reading on screens. If the answer to that question is little to none, or if you don’t see a significant difference between reading on screens and reading in print, I’d ask you to reconsider those positions.

If you’re in the second group, and you focus largely on reading in print with little focus on reading on screens, I’d ask that you reconsider that position as well.

Our students, and we, are reading more and more texts—for school, for work, for pleasure—on screens, and so it behooves us as teachers to squarely face that reality. At the risk of sounding overdramatic, I believe our students’ futures and our country’s future depend on us doing so.

“A Place of Apprehension Rather Than Comprehension”

One of the preeminent scholars on reading, Maryanne Wolf, the author of Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain, puts it well when she says of our understanding of digital reading: “We’re in a place of apprehension rather than comprehension” (qtd. in Konnikova). Indeed, though there continues to be much study of both digital and print reading, there has also been considerable anxiety about the decline of print and the effects that impaired reading could have on each of us and on our society as a whole, especially as most of us dive deeper into real-time, ever-shifting experiments on the effects of digital devices.

In his book, The Gutenberg Elegies, published in 1994 at the dawn of the Internet era, Sven Birkerts noted “some of the kinds of developments we might watch for as our ‘proto-electronic’ era yields to an all-electronic future,” each of which anticipates troubling aspects of our situation two decades later:

- Language erosion

- Flattening of historical perspectives

- The waning of the private self (128-130)

Warnings like Birkerts’ are worth paying attention to. Also, as we know, when any new medium gains traction, anxieties—some well-founded, some not—tend to abound, whether we’re talking about previous debates over the effects of television in the 20th Century; or the growing popularity of novels, newspapers, and magazines in the 19th; or even further back to Socrates worrying in Plato’s Phaedrus that if writing were to replace the oral tradition, it would “implant forgetfulness in [men’s] souls.”

In our present era, these anxieties sometimes break down into a kind of computer binary where we’re faced with an unsatisfactory choice between either print or digital texts. I’ll turn to an excerpt from a 2012 speech at the Nashville library by Margaret Atwood, she of the brilliant dystopian novels (and pithy tweets), for a useful challenge to that binary:

Margaret Atwood (Source: Poetry Foundation)

In [reading texts in] short form, [digital tools offer the virtues of] speed and ubiquity for small narrative bites. [Then in] long form, people split into three groups:

Number one: ‘I wouldn’t read online if you held a gun to my head.’

Number three: ‘You’re a troglodyte and live in a cave unless you tear up all your paper books and do nothing but read online.’

And most people are in the middle, and they say, ‘We want both.’ “

Right? So, given that reality, what’s a teacher of reading to do?

What We “Know”:

Differences in Print and Screen Reading

Now, reading on screens can mean a lot of different things, and there are a whole series of questions to take into account as we evaluate the differences between print and screen reading:

–Are we online or offline?

–What kind of device are we using, and how are we using it?

–Is the WiFi (and the possibility of distracting notifications) on or off?

–Is the screen backlit or does it employ the e-ink of an e-reader?

–What kind of text are we talking about: a lengthy novel that is native to print? A PDF of an academic article? An online article (like this one) full of hyperlinks and, perhaps, ringed by advertisements?

And so forth and so on. These are important distinctions, and I’ll try to make clear below which types of screen reading situations I’m referring to. Also, the multifarious ways of reading on screens point to just how complex an issue this is.

(And all of this is to say nothing of the rich new possibilities for reading, whether for critical reading or for pleasure, offered by digital texts, a subject that is beyond the scope of my argument here. Among the many, many things that have been written about that richness and about the comparisons of print and digital reading in this regard, I recommend taking a look at the following articles by N. Katherine Hayles and Paul LaFarge.)

However, after acknowledging those complications (and benefits!) of screen reading, there are some generalizations we can make.

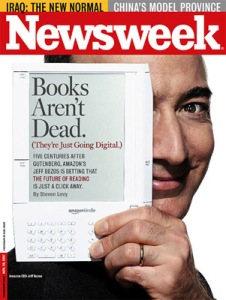

(Source: Amazon)

Among the most comprehensive books on this subject is Naomi Baron’s Words Onscreen: The Fate of Reading in a Digital World, which covers the history of the development of reading, details multiple studies on the subject, examines the screen and print reading landscape, and, importantly, includes her own surveys of student attitudes towards reading in the two media (more on those attitudes in a moment).

Early in her book, Baron notes the following:

“For over two decades, psychologists and reading specialists have been comparing how we read on screens versus in print. Studies have probed everything from proofreading skills and reading speed to comprehension and eye movement. Nearly all recent investigations are reporting essentially no differences” (12).

However, as Baron points out later in her book (and as she elaborated in a subsequent email exchange with me), these findings rely on laboratory conditions directly comparing screen and print reading that don’t fully capture the way we tend to read: “The investigations involve relatively brief readings followed by some version of comprehension or memory questions. What we don’t have—but sorely need—are data on what happens when people are asked to do close reading of continuous text….onscreen versus in print” (171).

However, if we consider our typical, everyday practices alongside the findings of other studies of screen reading—particularly of the way we tend to read on devices with connections to the Internet—I think we can agree that there are some strong indications that when we’re reading on most digital devices (think computers and smart phones especially) as compared to reading in print we tend to:

–be more easily distracted

–experience eye fatigue from back-lit screens

–be less inclined to read deeply than we might in print

–have less memory of and less comprehension of what we read

–have a harder time getting a holistic sense of the text

–have a lower tolerance for longer texts [reflected in the text-speak acronym TL;DR (Too long; didn’t read)]

(Source: English Language & Usage Stack Exchange)

Certainly this is the reporting of a substantial majority my own students, whom I ask every semester to reflect on the way they read in different media, and this tracks with the surveys of students both in the U.S. and abroad that Naomi Baron has conducted and reports in her book. In the work they do for school, students tend to associate reading in print with better learning outcomes.

Same Skills, Different Medium? Not Exactly

The question arises whether we need to continue to teach traditional literacies associated with print and then help students transfer those skills to the digital realm OR whether we ought to focus on cultivating the different kinds of literacies that reading on screens requires. The research of Julie Coiro of the University of Rhode Island suggests that the answer to both halves of that question is likely “Yes.”

For instance, the findings of one 2011 study that she conducted of the online reading comprehension of a group of seventh graders “support other research that suggests the processes skilled readers use to comprehend online text are both similar to and more complex than what previous research suggests is required to comprehend offline informational text” (Coiro 370). At the same time, the study also found positive correlations between offline and online reading comprehension.

Coiro also saw indications that students needed to have proficiency in newer, online reading skills (e.g. online searching, web page evaluation, negotiation of hyperlinks, etc.) before they could apply some of the skills traditionally associated with successful reading of printed text. Further, the results of the study indicated that “topic-specific prior knowledge” was important to successful reading comprehension for those students who had less skill in online reading, while this prior knowledge was less significant to the reading comprehension of students who had “average or high levels of online reading skills” (Coiro 374).

Coiro is assiduous in listing a series of qualifications for these findings, noting that there are a variety of possible interpretations, and that competency in “online reading” can mean a great many things dependent on the task and the assessment; she calls for further research. However, Coiro’s careful work is among the studies suggesting that students likely need distinct training in how to navigate, say, a book versus a web site in order for the critical reading skills applied to the former to be used fruitfully in the latter.

As Coiro has said elsewhere, “In reading on paper, you may have to monitor yourself once, to actually pick up the book….On the Internet, that monitoring and self-regulation cycle happens again and again” (qtd. in Konnikova). Teaching our students (and, again, ourselves) how to be better self-regulators is crucial to our success as screen readers—especially when we’re online.

Attitude and Belief as Self-Fulfilling Prophesy

As I said above, when I survey my students about the way they read for school and for pleasure, their replies track pretty closely with what Baron has found in the surveys of college students that she has conducted. When they read on screens, students tend to like:

–the convenience of being able to search within a text more easily and the ability to look up clarifying information online while they read;

–the portability and perceived environmental friendliness of digital texts (the latter is a debate for another time);

–and the lower economic cost compared to print.

Meanwhile, they tend to report that when they read printed texts, they:

–are more likely to re-read and to understand the text;

–have an easier time taking notes;

–are better able to focus;

–and are less likely to try to multitask.

Based on these pretty common reports by students, this would seem to indicate that they have found they perform demonstrably better as readers in school settings when they read in print. But is it so?

Last spring, I asked a group of 33 students in my reading and composition courses to complete a relatively simple assignment. I had them read Nicholas Carr’s 2008 article, “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” (Later expanded into his 2010 book, The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains.) I told them they could read the online version on The Atlantic’s web site, download the PDF via academic databases, or print out the article in either form, according to their preference. I then asked them to write a two- to three-page summary of the article, followed by a one-page response with their initial assessments of Carr’s arguments. Once they turned in the final draft, I also asked them to tell me in what form they had read the article and what they noticed about the way they read as they worked on the assignment.

Of the 33 students, 13 immediately printed the article and worked with that version, 11 read it entirely online, and the other 9 students did some mixture of online, PDF, or print reading that made it tougher to discern which medium they had used most prominently. Once I had graded the assignment, I looked at the scores of the purely online and print readers, and here’s what emerged:

Of the 13 who printed the article, the average grade on the paper was about a B-minus. (This group tended to include my weaker readers and writers.)

Of the 11 who read Carr’s article online, the average grade was an A-minus. (This group generally included the stronger readers and writers, as the grades would indicate.)

While acknowledging that this sample size isn’t remotely statistically significant, I find this result intriguing and wondered at the time how things had turned out this way—both what dictated the students’ choices of medium as well as how the respective groups performed on the assignment.

(Source: NPR)

A number of studies of students’ ways of approaching digital and paper texts provide a partial explanation of what may be going on.

In a study of Israeli college students, cognitive scientists Rakefet Ackerman and Morris Goldsmith compared the way the students performed on multiple-choice tests after reading two short texts: one printed and one a Microsoft Word file on a computer screen. In one experiment, the students were given a fixed amount of time to study, and performed about the same in their reading comprehension of the two types of texts. In a second experiment in which the students decided for themselves how long to study, the students performed much better on the test connected to reading on paper than they did on the test of their on-screen reading.

Ackerman and Goldsmith suggest that these results potentially point less to differences in the two media used for reading than they do to the metacognitive processes being employed by the students. In short, if readers perceive that screen reading can be employed for “effortful learning” in much the same way as they tend to perceive reading in print, then they may be able to self-regulate their reading as effectively on screen as they do on paper, at least so far as simple text (as opposed to hypertext) reading is concerned.

Bringing effort, or not, is partly down to mindset, of course. In a 2001 study that Baron briefly references in her book, a group of college students was examined to see how they performed when they read printed texts “for study purposes or for entertainment.” Unsurprisingly, “Students reading in study mode were better at making inferences, generating paraphrases, and remembering the text’s content” (Baron 161). This makes perfect sense. Now if we consider that students use their laptops not only for work but also for gaming or to watch funny YouTube channels or to video chat with friends, and that they turn to their smart phones all the time for Snapchatting, Instragramming, texting and the like, we can easily see the association between these devices and entertainment, an enticing potential distraction that is ever present when the student turns to those same devices to try to read in more than a cursory way. To engage in the effortful work of reading, that constant self-monitoring that Coiro speaks of comes into play.

A 2015 study conducted by German researcher Johannes Naumann helps further this point. Naumann examined the data from a 2009 OECD PISA Digital Reading Assessment of over 29,000 high school students from 17 different countries. He examined how students navigated through hyperlinked pages to complete various information-seeking tasks, some of which required that students visit only one or a few pages in order to be successful and some of which required the negotiation of multiple pages.

Those students who were more accustomed to seeking information online had more success at navigating and at completing the tasks successfully and efficiently (i.e. not spending a lot of time clicking irrelevant links) than did those who were accustomed to using online spaces mostly as places for social engagement. These differences in success were more pronounced the more difficult the task became. Further, the students with greater print reading skill tended to perform better on these assessments.

His findings suggest the importance of both experience with navigating online text for more than social purposes and to the importance of having a mindset of “information engagement” for a student to have greater likelihood of success as a strong online reader. (For more on these and other studies, see the annotated bibliography I mentioned at the beginning of this post.)

And Now a Word from a Successful Online Reader

A final note on that assignment I asked my own students to do last year. One of my students provided a glimpse of some of what might have been going on for her and the other successful online readers in my class in the reflection she wrote afterward:

“I ended up reading [Carr’s article] online….I read during my research…that we can condition our mind not to be affected by the fact that we are reading online. In a sense, that if we approach…[what] we are reading [in this way], we can get as much out of it as if we [were] read[ing it] in print. So I wanted to try. I told myself that I was [going to] focus on the reading, and read it as if I was doing so in print so that I [could write] an accurate summary….”

After talking about her process a bit, she went on:

“It took me much longer just to plot…[Carr’s] main ideas, and even when I thought I had them, I still had to go back to the article continuously. I did not make annotations [on the text itself], which I [always] do [when I read] in print. But it was interesting to see…what changed when I approach[ed] an online article with the mindset that I [was] reading it [as if it were in] print. I definitely know now that no matter what, reading [in print works] better for me when doing assignments [like this one].”

That’s the kind of self-awareness I’d love all of our students to generate: not that they must read in one or the other medium to achieve a certain result, but to recognize their own best practices and to read mindfully, no matter the medium.

You’ll be completely unsurprised to learn that she earned an A on her paper.

Suggested Steps for Helping Students to Read Well on Screens

“Enough already! What do I do now?” you fellow teachers of critical reading may be wondering. I’m wondering too. The best approach to reading on screens is hardly a settled question, and will no doubt continue to change as the technology shifts around us. However, I do have a few suggestions, and would love to hear yours too.

First, I direct you to the aforementioned pages on this subject that my Berkeley colleague, Donnett Flash, and I put together. Also, here’s a quick (and evolving) handout (Read Well On Screens and Prosper) I’ve been giving to all my students, and a quicker list version I’ve given to fellow faculty: (Digital Reading Suggestions for Teachers).

For my purposes today, however, I’ll emphasize a few things:

*Help students to cultivate a screen reading mindset that they’ve got to bring effort, and effort of particular types, to be able to read successfully on digital devices. Perhaps most prominent among these practices is that they need to reduce distractions as much as possible and resist the medium’s associations with speed, efficiency, TL;DR, and entertainment. Power browsing, skimming, scrolling, and reading for gist are useful but they aren’t everything, and neither should they be the only thing.

*Create self-reflective screen reading assignments that will help students to be more self-aware and to identify their own best practices.

*Think carefully about how you’ll employ digital readings in and outside the classroom. Particularly with younger readers, do not substitute digital readings for print if you don’t plan on addressing the differences between them.

*Discuss, model, and reinforce screen reading skills explicitly.

*Identify and advocate for new technologies and practices that will deepen screen reading skills. And then tell me what they are.

*Learn from your students. Students are already discovering the technologies and approaches that help them to concentrate when they’re in “study mode.” Many of my own students employ ad blockers when they are online, or use applications like Be Focused Pro and Self Control to prevent themselves from getting distracted. They are mindful of how they need to arrange themselves physically—and how far away certain of their devices need to be—to be able to read well. Keep a record of these technologies and practices, and mark the best ones.

Reading is Fundamental: Toward Democratization and not Gentrification

I hardly have to preach to you, the converted, on the virtues of reading generally and the importance of helping students to read well on screens in particular, but I’m going to do it anyway.

We’ve all seen students coming into our classrooms with different, sometimes radically different, levels of preparation for college-level reading and writing. This often maps onto larger societal divisions between the haves and have-nots: those who come from wealthier communities with better equipped schools and those who do not; those who have long training and practice at reading and those who do not; those who have better access to and familiarity with digital technologies and those who do not. College is a place where we try to help close these gaps and reduce the inequality that plagues our country.

Focusing on reading well is ever more important now in a time of rising inequality, of difficulty at discerning real news from fake, and of divisiveness in a political landscape in which empathy is on the decline and misunderstanding is ascendant.

Teaching students of all backgrounds to read well on screens is a democratizing practice. It ensures that such pursuits—and the benefits that flow from them—don’t turn reading into a gentrified activity whose advantages are available only to a privileged few as we spend more and more of our time reading (and talking and watching and living) on screens, cordoned off in shrinking electronic worlds of our own making.

In this same vein, I’ll let the novelist Caleb Crain have the last word here as he reminds us of what is at stake:

“[T]he N.E.A. reports that readers are more likely than non-readers to play sports, exercise, visit art museums, attend theatre, paint, go to music events, take photographs…volunteer….[and] vote. Perhaps readers venture so readily outside because what they experience in solitude gives them confidence. Perhaps reading is a prototype of independence….Such a habit might be quite dangerous for a democracy to lose.”

Works Cited

One more time: For an annotated bibliography about these and other sources on digital/screen reading, I direct you here. In the meantime, here’s where to find the sources discussed in this post.

Baron, Naomi. Words Onscreen: The Fate of Reading in a Digital World. New York: Oxford UP, 2015. Print.

Birkerts, Sven. The Gutenberg Elegies: The Fate of Reading in an Electronic Age. New York: Fawcett Columbine, 1994. Print.

Carr, Nicholas. “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” The Atlantic. The Atlantic. 1 July 2008. Web.

—. The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains. New York: Norton, 2010. Print.

Coiro, Julie. “Predicting Reading Comprehension on the Internet: Contributions of Offline Reading Skills, Online Reading Skills, and Prior Knowledge.” Journal of Literacy Research 43.4 (2011): 352-392. Sage Publications. Web.

Crain, Caleb. “Twilight of the Books.” The New Yorker. 24 Dec. 2007. Web.

Konnikova, Maria. “Being a Better Online reader.” The New Yorker. Newyorker.com 16 July 2014. Web.

La Farge, Paul. “The Deep Space of Digital Reading.” Nautilus. nautil.us. 7 Jan 2016. Web.

Naumann, Johannes. “A Model of Online Reading Engagement: Linking engagement, navigation, and performance in digital reading.” Computers in Human Behavior. 53 (2015): 263-277.

Wolf, Maryanne. Proust and the Squid. New York: Harper Collins, 2007. Print.